Holzer creates text-based art that addresses social and political issues. She is known for large-scale displays in public spaces presented in the format of LED billboards and projections. While these works often blend in among advertisements, the content grabs attention by subverting expectations. Aphorisms such as “Abuse of power comes as no surprise” and “Protect me from what I want” have also appeared on posters, packaging and clothing.

Whether questioning consumerist impulses, power, or death and disease, Holzer’s use of language provokes a gut response in the viewer.

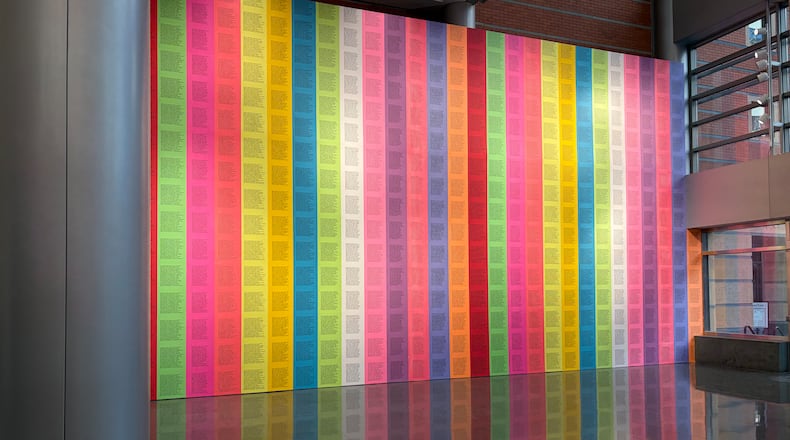

In the Weston installation, “Inflammatory Essays” consists of 100-word paragraphs printed on over 400 brightly colored backgrounds and arranged floor-to-ceiling in a grid formation. Each essay is approximately the size of a sheet of ubiquitous printer paper.

The short texts read as indignant declarations, asking the viewer — are these phrasings the voice of the artist? Are they meant to cull a shared sentiment of rage and disappointment in systems of power? Or are they the musings of some unhinged person?

“You get amazing sensations from guns,” reads one.

“There may be some accidents along the path to self-expression and self-determination,” it continues.

According to The Weston, “these texts do not mirror Holzer’s own sentiments, but are rather drawn from the writings of anarchists, dictators, and revolutionaries around the world. The voices include Emma Goldman, Adolf Hitler, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Tse-tung and Leon Trotsky.”

The confrontational language can come across as conspiratorial diary entries or prompts for aggression. To some, they might be triggering. To others, they might have a tone of voyeurism, a search for meaning in the terrifying and desperate acts of violence that play out regularly in our schools and places of worship. Eventually, the repetition in the essays begins to dull the shock. Art imitates life.

Credit: Contributed

Credit: Contributed

In a 2016 interview with Even Magazine, Holzer stated, “I have found it necessary and proper at times to be careful. I’m pro-expression but not pro-murder. I think it is utterly irresponsible and reprehensible to incite violence…Once we get rolling, it’s hard to stop.”

So what do you think, reader? Are Holzer’s texts works of appropriation? Are they critiques of the power structure? Or are they meant to stir emotion in an increasingly apathetic, screen-rotted society?

Emily Hanako Momohara: ‘Grounded’

Emily Hanako Momohara is a visual artist and filmmaker who until recently lived and worked in Cincinnati. She is now Endowed Chair in Animation and Media Arts at Maryland Institute College of Art.

The language of violence at play in Holzer’s texts have, in some sense, a shared foundation with Momohara’s body of work, “Grounded”, on view in The Weston’s lower galleries. They both point towards the legacy of violence in American society.

Momohara began these portrait photographs in the shadow of the 2021 Atlanta Spa Shootings, in which the majority of victims were women of Asian descent. The shooting, against the backdrop of rising anti-Asian sentiment in the country, in part gave rise to the Stop Asian Hate movement.

The portraits depict Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women and families facing the camera while holding family photographs of their migrant forbearers. The imagery depicts U.S. locations important to those portrayed, creating a connection to place and making clear their American familial roots. The portraits are paired with landscape backgrounds in a collage-like manner. The photograph within a photograph has a nesting doll quality, representing generations and the passing of time.

Credit: Contributed

Credit: Contributed

According to the Weston, the images “seek to elevate immigration narratives and challenge stereotypes that have shrouded the identities of AAPI women, including the artist herself”. Referenced are personal journeys ranging from fleeing the Chinese Cultural Revolution to immigrating for college.

The title “Grounded” can take on various meanings, all rooted in a sense of place. Psychologically, to be grounded is to feel stable and connected to the present moment. Suggesting a state of emotional regulation, it describes control during stressful situations.

Spiritually, to be grounded is to be in deep physical contact with the Earth; there is an implication that one has a sense of purpose and inner worth.

Of course, being grounded takes on a very different meaning for a rebellious teenager. Though also rooted in place, it commands you stay where you are, prisoner-like.

In a time when immigrants to the U.S. are under increased scrutiny and the National Guard is being sent in to police various domestic cities, Momohara’s work takes on added weight.

Two generations of the artist’s family, who is of Japanese American heritage, were incarcerated under Executive Order 9066. Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1942, it authorized designated military areas in the U.S., leading to the mass forced relocation and incarceration of approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, to internment camps.

In some cases, Momohara’s subjects are the first individuals in their family to have immigrated at the turn of the twentieth century, beginning five generations of American family legacy.

HOW TO GO

What: Jenny Holzer: “Inflammatory Essays” and Emily Hanako “Momohara: Grounded”

Where: Weston Art Gallery, 650 Walnut St., Cincinnati

When: 10 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; noon-5 p.m. Sunday. Through Nov. 2

Admission: Free

More info: westonartgallery.com; 513-977-4165

About the Author